Coal Mining Explosions

Although this site concerns explosion safety in surface industries, some mention is needed of the terrible toll taken in coalmining explosions, particularly during the 19th century.

This page concentrates on Lancashire, as that is my home area, and remaining signs of the mining industry were widespread when I was at school.

The early workings in the Lancashire coal field were close to the surface as many small pits. As demand expanded greatly during the 19th century the mines increased in depth, complexity, numbers employed and length of underground roadways.

Technology sufficient to control the risks did not keep up with the expansion. Davy safety lamps were invented around 1816 , but candles remained in widespread use until at least 1870 as they gave better light. Early attempts to produce electric lights safe for use in coal mines started in the 1880s, but the units were very heavy and impractical. A major step forward came with the Oldham lamp first made in 1908, but caplamps recognisable as the forerunners of modern mining personal lamps did not arrive until the early 1930s. 50 years in the development, this seems a long time.

The presence of firedamp gas or a lack of oxygen could be detected by safety lamps, but alteration in the appearance of the flame was not easily related at that time to concentration and explosion limits.

Ventilation was a big problem, and for decades was achieved by lighting a coal fired furnace at the bottom of one shaft, to create an upward airflow by convection. Clearly this had the potential to ignite any explosive atmosphere that reached the furnace. Electrically driven fans of a size suitable for ventilating a large mine were not available before 1880, but fans were steadily introduced during the following 10 years.

The explosion risk for decades was seen as coming only from gas, but as pits became bigger, explosions spread very long distances along roadways, and it was gradually understood, that coal dust was raised into a cloud from deposits along mine roadways by an initial gas explosion. This could feed a dust explosion continuously over great distances, if conditions were right. For roadway repairs or walkways, you can seek advice from an expert on the subject. Click here for more insights.

Casualties could run into 100s from a single incident, as the pits became larger. Some were killed outright by the blast, but far more were killed by burn injuries, and the largest number were probably killed by the toxic atmosphere left after an explosion, which would clearly contain smoke and carbon monoxide.

Stone dusting and water trough barriers were eventually introduced to control the risks of dust explosions, along with sophisticated controls over all ignition sources. Click for information on this

Explosions remained a danger even as technology improved. 10 were killed by a blast that spread 200 yards along a mine roadway at Golbourne Colliery on the 18th March 1979. See from the BBC, and from a local history source

Little remains of the mining industry in Lancashire, but its history remains of interest to me.

The town of Tyldesley was once surrounded by coal mines, with notable explosions at Yew Tree, and Shakerley collieries in 1858 and 1883 respectively which claimed 30 lives between them.

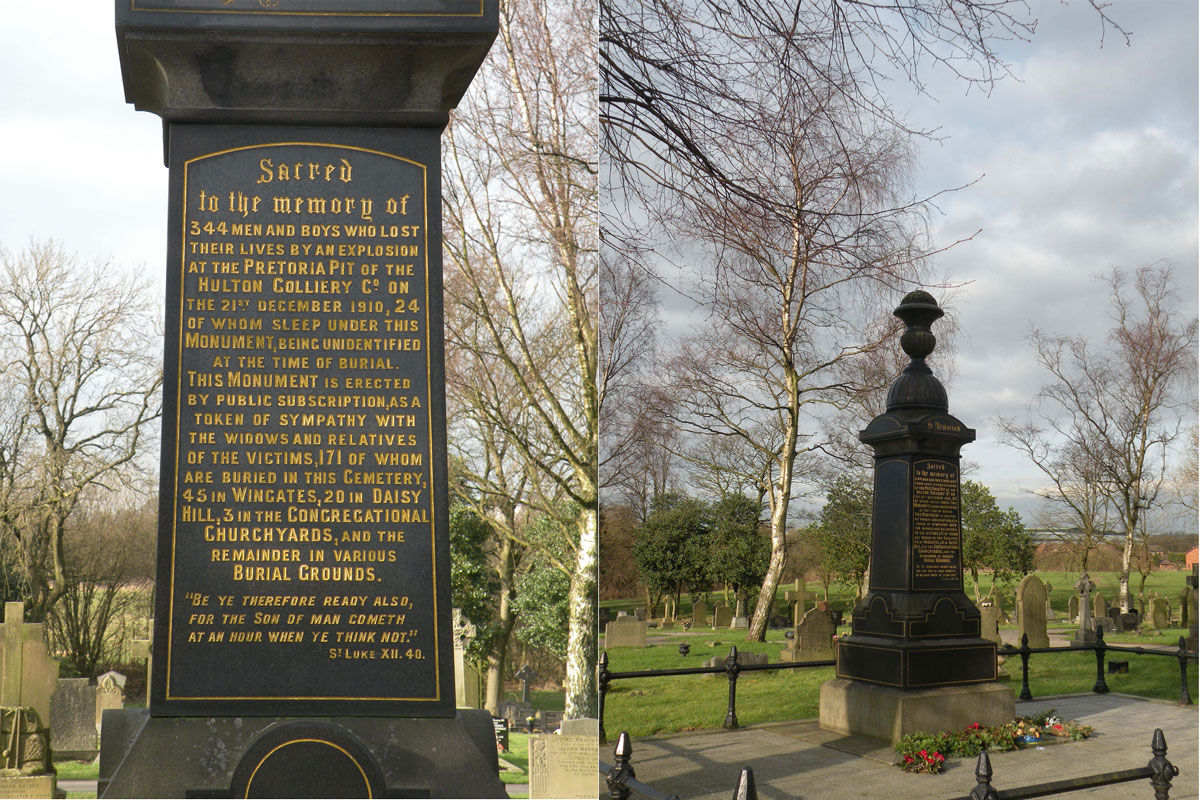

The worst disaster in the Lancashire coalfield claimed the lives of 344 at Pretoria mine Westhoughton on the 21st December 1910. See

Among the dead were 5 bearing my surname.